Common Agricultural Policy

| European Union |

This article is part of the series: |

|

Policies and issues

|

|

Foreign relations

|

The common agricultural policy (CAP) is a system of European Union agricultural subsidies and programmes. It represents 48% of the EU's budget, €49.8 billion in 2006 (up from €48.5 billion in 2005).[1]

The CAP combines a direct subsidy payment for crops and land which may be cultivated with price support mechanisms, including guaranteed minimum prices, import tariffs and quotas on certain goods from outside the EU. Reforms of the system are currently underway reducing import controls and transferring subsidy to land stewardship rather than specific crop production (phased from 2004 to 2012). Detailed implementation of the scheme varies in different member countries of the EU.

Until 1992 the agriculture expenditure of the European Union represented nearly 49% of the EU's budget. By 2013, the share of traditional CAP spending is projected to decrease significantly to 32%, following a decrease in real terms in the current financing period. In contrast, the amounts for the EU's Regional Policy represented 17% of the EU budget in 1988. They will more than double to reach almost 36% in 2013.[2]

The aim of the common agricultural policy (CAP) is to provide farmers with a reasonable standard of living, consumers with quality food at fair prices and to preserve rural heritage. However, there has been considerable criticism of CAP.

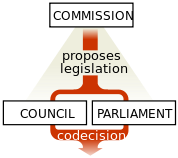

Overview of the CAP

The creation of a common agricultural policy was proposed by the European Commission. It followed the signing of the Treaty of Rome in 1957, which established the Common Market. The six member states individually strongly intervened in their agricultural sectors, in particular with regard to what was produced, maintaining prices for goods and how farming was organised. This intervention posed an obstacle to free trade in goods while the rules continued to differ from state to state, since freedom of trade would interfere with the intervention policies. Some Member States, in particular France, and all farming professional organisations wanted to maintain strong state intervention in agriculture. This could therefore only be achieved if policies were harmonised and transferred to the European Community level. By 1962, three major principles had been established to guide the CAP: market unity, community preference and financial solidarity. Since then, the CAP has been a central element in the European institutional system.

The CAP is often explained[3] as the result of a political compromise between France and Germany: German industry would have access to the French market; in exchange, Germany would help pay for France's farmers. Germany is still the largest net contributor into the EU budget; however, as of 2005 France is also a net contributor and the more agriculture-focused Spain, Greece and Portugal are the biggest beneficiaries. Meanwhile particularly urbanised member states where agriculture compromises only a very small part of the economy such as the Netherlands and the United Kingdom are much smaller beneficiaries and the CAP is often unpopular with the national governments. Transitional rules apply to the newly admitted member states which limit the subsidies which they currently receive.

Objectives

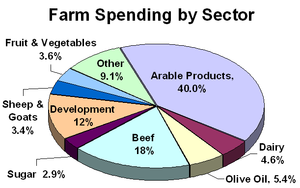

Sectors covered by the CAP

The common agricultural policy price intervention covers only certain agricultural products:

- cereal, rice, potatoes

- oil

- dried fodder

- milk and milk products, wine, honey

- beef and veal, poultry meat and eggs, pig meat, sheep / lamb meat and goat meat

- sugar

- fruit and vegetables

- cotton

- peas, field beans

- sweet lupins

- olives

- seed flax

- silkworms

- fibre flax

- hemp

- tobacco

- hops

- seeds

- flowers and live plants

- animal feed stuffs

The coverage of products in the external trade regime is more extensive than the coverage of the CAP regime. This is to limit competition between EU products and alternative external goods (for example, lychee juice could potentially compete with orange juice).

The initial objectives were set out in Article 39 of the Treaty of Rome:[1]

- to increase productivity, by promoting technical progress and ensuring the optimum use of the factors of production, in particular labour;

- to ensure a fair standard of living for the agricultural Community;

- to stabilise markets;

- to secure availability of supplies;

- to provide consumers with food at reasonable prices.

The CAP recognised the need to take account of the social structure of agriculture and of the structural and natural disparities between the various agricultural regions and to effect the appropriate adjustments by degrees.

CAP is an integrated system of measures which works by maintaining commodity price levels within the EU and by subsidising production. There are a number of mechanisms:

- Import levies are applied to specified goods imported into the EU. These are set at a level to raise the World market price up to the EU target price. The target price is chosen as the maximum desirable price for those goods within the EU.

- Import quotas are used as a means of restricting the amount of food being imported into the EU. Some non member countries have negotiated quotas which allow them to sell particular goods within the EU without tariffs. This notably applies to countries which had a traditional trade link with a member country.

- An internal intervention price is set. If the internal market price falls below the intervention level then the EU will buy up goods to raise the price to the intervention level. The intervention price is set lower than the target price. The internal market price can only vary in the range between the intervention price and target price.

- Direct subsidies are paid to farmers. This was originally intended to encourage farmers to choose to grow those crops attracting subsidies and maintain home-grown supplies. Subsidies were generally paid on the area of land growing a particular crop, rather than on the total amount of crop produced. Reforms implemented from 2005 are phasing out specific subsidies in favour of flat-rate payments based only on the area of land in cultivation, and for adopting environmentally beneficial farming methods. The change is intended to give farmers more freedom to choose for themselves those crops most in demand and reduce the economic incentive to overproduce.

- Production quotas and 'set-aside' payments were introduced in an effort to prevent overproduction of some foods (for example, milk, grain, wine) that attracted subsidies well in excess of market prices. The need to store and dispose of excess produce was wasteful of resources and brought the CAP into disrepute. A secondary market evolved, especially in the sale of milk quotas, whilst some farmers made imaginative use of 'set-aside', for example, setting aside land which was difficult to farm. Currently set-aside has been suspended, subject to further decision about its future, following rising prices for some commodities and increasing interest in growing biofuels[4].

The change in subsidies is intended to be completed by 2011, but individual governments have some freedom to decide how the new scheme will be introduced. The UK government has decided to run a dual system of subsidies, each year transferring a larger proportion of the total payment to the new scheme. Payments under the old scheme were frozen at their levels averaged over 2002-2003 and reduce each subsequent year. This allows farmers a period where their income is maintained, but which they can use to change farm practices to accord with the new regime. Other governments have chosen to wait, and change the system in one go at the latest possible time. Governments also have limited discretion to continue to direct a small proportion of the total subsidy to support specific crops. Alterations to the qualifying rules meant that many small landowners became eligible to apply for grants and the Rural Payments Agency in the UK received double the previous number of applications (110,000).

The CAP also aims to promote legislative harmonisation within the Community. Differing laws in member countries can create problems for anyone seeking to trade between countries. Examples are regulations on permitted preservatives or food coloring, labelling regulations, use of hormones or other drugs in livestock intended for human consumption and disease control (e.g. during the foot and mouth disease outbreak in the United Kingdom, Ireland and the Netherlands), animal welfare regulations. The process of removing all hidden legislative barriers to trade is still incomplete.

The CAP is funded by the European Agricultural Guidance and Guarantee Fund (EAGGF) of the EU. CAP reform has steadily lowered its share of the EU budget but it still accounts for nearly half EU expenditure. In recent years France has benefited the most from these subsidies. The new accession countries which joined the EU in 2004 have large farm sectors and would have overtaken France as chief beneficiary, but for transitional regulations limiting the subsidies which they receive. The continuing problem of how subsidies for these countries will be paid when they become eligible has already led to French concessions on reform of the CAP. Further concessions will inevitably be necessary to balance the budget.

History of the CAP

The common agricultural policy was born in the late 1950s and early 1960s when the founding members of the EC had just emerged from over a decade of severe food shortages during and after the Second World War. As part of building a common market, tariffs on agricultural products would have to be removed. However, due to the political clout of farmers, and the sensitivity of the issue, it would take many years before the CAP was fully implemented.

Beginnings of the CAP

The Treaty of Rome defined the general objectives of a common agricultural policy. The principles of the common agricultural policy (CAP) were set out at the Stresa Conference in July 1958. In 1960, the CAP mechanisms were adopted by the six founding Member States and two years later, in 1962, the CAP came into force. The creation of a common agricultural policy was proposed in 1960 by the European Commission. It followed the signing of the Treaty of Rome in 1957, which established the Common Market. The six member states individually strongly intervened in their agricultural sectors, in particular with regard to what was produced, maintaining prices for goods and how farming was organised. This intervention posed an obstacle to free trade in goods while the rules continued to differ from state to state, since freedom of trade would interfere with the intervention policies. Some Member States, in particular France, and all farming professional organisations wanted to maintain strong state intervention in agriculture. This could therefore only be achieved if policies were harmonised and transferred to the European Community level.

By 1962, three principles had been established to guide the CAP: market unity, community preference and financial solidarity. Since then, the CAP has been a central element in the European institutional system.

Evolution and reform

The CAP has always been a difficult area of EU policy to reform; this is a problem that began in the 1960s and one that continues to the present day, albeit less severely. The Agricultural Council is the main decision-making body for CAP affairs. Above all, however, unanimity is needed for most serious CAP reform votes, resulting in rare and gradual change. Outside Brussels proper, the farming lobby's power has been a factor determining EU agricultural policy since the earliest days of integration. This lobby's power has decreased markedly since the 1980s.

In recent times change has been more forthcoming, due to external trade demands and intrusion in common agricultural policy affairs by other parts of the EU policy framework, such as consumer advocate working groups and the environmental departments of the Union. In addition Euroscepticism in states such as the UK and Denmark is fed in part by the CAP, which Eurosceptics consider detrimental to their economies.

Proponents claim that the CAP is an exceptional economic sector as protects the "rural way of life", although it is recognised that this has an impact on world poverty.[5]

Early attempts at reforms

The Mansholt Plan

The Mansholt Plan was a 1960s idea that sought to remove small farmers from the land and to consolidate farming into a larger, more efficient industry. Farming's special status, and above all the extremely powerful farming lobbies across the Continent saw the Plan disappear from the Union's objectives.

On 21 December 1968, Sicco Mansholt (European Commissioner for Agriculture), sent a memorandum to the Council of Ministers concerning agricultural reform in the European Community.[6] This long-term plan, also known as the ‘1980 Agricultural Programme’ or the ‘Report of the Gaichel Group’, named after the village in Luxembourg where it had been prepared, laid the foundations for a new social and structural policy for European agriculture.

The Mansholt Plan noted the limits to a policy of price and market support. It predicted the imbalance that would occur in certain markets unless the Community undertook to reduce its land under cultivation by at least 5 million hectares. Mansholt also noted that the standard of living of farmers had not improved since the implementation of the CAP, despite an increase in production and permanent increases in Community expenditure. He therefore suggested that production methods should be reformed and modernised and that small farms, which were bound to disappear sooner or later, according to Community experts, should be increased in size. The aim of the Plan was to encourage nearly five million farmers to give up farming. That would make it possible to redistribute their land and increase the size of the remaining family farms. Farms were considered viable if they could guarantee for their owners an average annual income comparable to that of all the other workers in the region. In addition to vocational training measures, Mansholt also provided for welfare programmes to cover retraining and early retirement. Finally, he called on the Member States to limit direct aid to unprofitable farms.

Faced with the increasingly angry reaction of the agricultural community, Sicco Mansholt was soon forced to reduce the scope of some of his proposals. Ultimately, the Mansholt Plan was reduced to just three European directives which, in 1972, concerned the modernisation of agricultural holdings, the abandonment of farming and the training of farmers.

Between Mansholt and MacSharry

Hurt by the failure of Mansholt, would-be reformers were mostly absent throughout the 1970s, and reform proposals were few and far between. A system called "Agrimoney" was introduced as part of the fledgling EMU project, but was deemed a failure and did not stimulate further reforms.

The 1980s was the decade that saw the first true reforms of the CAP, foreshadowing further development from 1992 onwards. The influence of the farming bloc declined, and with it, reformers were emboldened. Environmentalists garnered great support in reforming the CAP, but it was financial matters that ultimately tipped the balance: due to huge overproduction the CAP was becoming expensive and wasteful. These factors combined saw the introduction of a quota on dairy production in 1984, and finally, in 1988, a ceiling on EU expenditure to farmers. However, the basis of the CAP remained in place, and not until 1992 did CAP reformers begin to work in earnest.

1992

In 1992, the MacSharry reforms (named after the European Commissioner for Agriculture, Ray MacSharry) were created to limit rising production, while at the same time adjusting to the trend toward a more free agricultural market. The reforms reduced levels of support by 29% for cereals and 15% for beef. They also created 'set-aside' payments to withdraw land from production, payments to limit stocking levels, and introduced measures to encourage retirement and forestation.

Since the MacSharry reforms, cereal prices have been closer to the equilibrium level, there is greater transparency in costs of agricultural support and the 'de-coupling' of income support from production support has begun. However, the administrative complexity involved invites fraud, and the associated problems of the CAP are far from being corrected.

It is worth noting that one of the factors behind the 1992 reforms was the need to reach agreement with the EU's external trade partners at the Uruguay round of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) talks with regards to agricultural subsidies.

Modern reforms

The current areas that are issues of reform in EU agriculture are: lowering prices, ensuring food safety and quality, and guaranteeing stability of farmers' incomes. Other issues are environmental pollution, animal welfare, and finding alternative income opportunities for farmers. Some of these issues are the responsibility of the member states.

1999

The 'Agenda 2000' reforms divided the CAP into two 'Pillars': production support and rural development. Several rural development measures were introduced including diversification, setting up producer groups and support for young farmers. Agri-environment schemes became compulsory for every Member State (Dinan 2005: 367). The market support prices for cereals, milk and milk products and beef and veal were step-wise reduced while direct coupled payments to farmers were increased. Payments for major arable crops as cereals and oilseeds were harmonized.[7]

European Commission Report (2003)

A 2003 report, commissioned by the European Commission, by a group of experts led by Belgian economist André Sapir stated that the budget structure was a “historical relic”.[8] The report suggested a reconsideration of EU policy, redirecting expenditure towards measures intended to increase wealth creation and cohesion of the EU. As a significant proportion of the budget is currently spent on agriculture, and there is little prospect of the budget being increased, this would necessitate reducing CAP expenditure. The report largely concerned itself discussing alternative measures more useful to the EU, rather than discussing the CAP, but it did also suggest that farm aid would be administered more effectively by member countries on an individual basis.

The report's findings were largely ignored. Instead, CAP spending was kept within the remit of the EU - and France led an effort to agree a fixed arrangement for CAP spending that would not be changed until 2012. This was made possible by advance agreement to this approach with Germany. It is this agreement that the UK currently wishes to see re-opened, both in their efforts to defend the UK position on the UK rebate and also given that the UK is in favour of lowering barriers to entry for third world agricultural exporters.[9]

Decoupling (2003)

On 26 June 2003, EU farm ministers adopted a fundamental reform of the CAP, based on "decoupling" subsidies from particular crops. (Though Member States may choose to maintain a limited amount of specific subsidy.) The new "single farm payments" are subject to "cross-compliance" conditions relating to environmental, food safety and animal welfare standards. Many of these were already either good practice recommendations or separate legal requirements regulating farm activities. The aim is to make more money available for environmental quality or animal welfare programmes.

Details of the UK scheme were still being decided at its introductory date of May 2005. Details of the scheme in each member country may be varied subject to outlines issued by the EU. In England the single payment scheme provides a single flat rate payment of around £230 per hectare for maintaining land in cultivatable condition. In Scotland payments are based on a historical basis and can vary widely. The new scheme allows for much wider non-production use of land which may still receive the environmental element of the support. Additional payments are available if land is managed in a prescribed environmental manner.

The overall EU and national budgets for subsidy have been capped. This will prevent a situation where the EU is required to spend more on the CAP than its limited budget has.

The reforms enter into force in 2004-2005. (Member States may apply for a transitional period delaying the reform in their country to 2007 and phasing in reforms up to 2012) [10]

Sugar regime reform (2005-2006)

One of the crops subsidised by the CAP is sugar produced from sugar beet; the EU is by far the largest sugar beet producer in the world, with annual production at 17 million metric tons. This compares to levels produced by Brazil and India, the two largest producers of sugar from sugar cane.[11]

Sugar was not included in the 1992 MacSherry reform, or in the 1999 Agenda 2000 decisions; sugar was also subject to a phase-in (to 2009) under the Everything But Arms trade deal giving market access to least developed countries. As of 21 February 2006, the EU has decided to reduce the guaranteed price of sugar by 36% over four years, starting in 2006. European production was projected to fall sharply. According to the EU, this is the first serious reform of sugar under the CAP for 40 years.[12][13] Under the Sugar Protocol to the Lome Convention, nineteen ACP countries export sugar to the EU,[14] and will be affected by price reductions on the EU market.

These proposals followed the WTO appellate body largely upholding on 28 April 2005 the initial decision against the EU sugar regime.[15]

An aim of this policy change is to allow easier and more profitable access to European markets for emerging economies. Critics, such as "EUPolitix", contend that this is not an altruistic move nor an idealistic shift from the EU, who are instead acting only in accordance with the wishes of the WTO, who supported challenges on sugar dumping by the EU from Australia, Thailand and Brazil. Another point of contention is that those countries who currently receive preferential treatment from EU member states - often due to colonial ties - as part of the ACP group may stand to lose out.[16]

Proposed direct subsidy limits (2007)

In the autumn of 2007 the European Commission was reported to be considering a proposal to limit subsidies to individual landowners and factory farms to around £300,000. Some factory farms and estates of rich people would be affected in the UK, as there are over 20 farms/estates which receive £500,000 or more from the EU.[17][18] Similar attempts have been unsuccessful in the past and were opposed in the UK by two strong lobbying organizations the Country Land and Business Association and the National Farmers Union. Germany, which has large collective farms still in operation in what was East Germany also vigorously opposed changes which were marketed as "reforms". The proposal was reportedly submitted for consultation with EU member states on November 20, 2007.[19]

Post-2013 CAP

The next CAP reform will coincide with a new EU budget. The current EU long-term budget runs from 2007 to 2013. The next long-term budget (also called 'financial perspectives'), starting in 2014, is currently under negotiation. Main issues include reductions in the size of the future CAP budget, the phase-out or reform of the Single Farm Payment (for direct income support to farmers) and the strengthening of targeted payments for public goods (rewarding farmers e.g. for environmental stewardship services). An initial step in the debate has been the Budget Review conference, organized by the European Commission, in November 2008.[20] Another milestone has been the publication, in November 2009, of an declaration by leading agricultural economists from all over Europe advocating “A Common Agricultural Policy for European Public Goods“.[21] The declaration proposes to remove all blanket subsidies that stimulate production and support farm incomes. Instead, subsidies should be focused exclusively on the provision of public goods, notably to fight climate change, preserve biodiversity and manage water resources.

In March 2010 the European Commissioner for the Environment Janez Potočnik called for a Common Agricultural and Environmental Policy, saying that the CAP should be greened; that is should improve sustainability, soil quality, water quality and efficiency. The policy should contribute to global food security and provide green products.[22]

Criticism of the CAP

The CAP has been roundly criticised by many diverse interests since its inception. Criticism has been wide-ranging, and even the European Commission has long been persuaded of the numerous defects of the policy. In May 2007, Sweden became the first EU country to take the position that all EU farm subsidies should be abolished (except those related to environmental protection) [23].

Anti-development

Criticism of the CAP has united some supporters of neoliberal globalisation with the alter-globalisation movement in that it is argued that these subsidies, like those of the USA and other Western states, add to the problem of what is sometimes called Fortress Europe; the West spends high amounts on agricultural subsidies every year, which amounts to unfair competition. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries' total agricultural subsidies amount to more than the official development assistance from OECD countries to developing countries. Support to farmers in OECD countries totals 280 billion USD annually. By contrast, official development assistance amounted to 80 billion USD in 2004. OECD analysts estimate that cutting agricultural tariffs and subsidies by 50% would add an extra 26 billion USD to annual world income, equivalent to just over four dollars a year for every person on the globe. [24]

Oversupply and its redistribution

To perpetuate the viability of European agriculture in its current state, the CAP-mandated demand for certain farm products is set at a high level compared with demand in the free market (see CAP as a form of State intervention). This leads to the European Union purchasing millions of tonnes of surplus output every year at the stated guaranteed market price, and storing this produce in large quantities (leading to what critics have called 'butter mountains' and 'milk lakes'), before selling the produce wholesale to developing nations.[25] In 2007 in response to a parliamentary written question the UK government revealed that over the preceding year the EU Public Stock had amassed "13,476,812 tonnes of cereal, rice, sugar and milk products and 3,529,002 hectolitres of alcohol/wine”, although the EU has claimed this level of oversupply is unlikely to be repeated. In January 2009 the EU had a current store of 717,810 tonnes of cereals, 41,422 tonnes of sugar and a 2.3 million hectolitre 'wine lake'. The EU will also purchase and further subsidise the export of 30,000 tonnes of butter and 109,000 tonnes of powdered milk to the third world.[25][26]

By adding import tariffs to agricultural goods exported by farmers in developing countries, whilst at the same time undercutting them in their domestic market where European oversupply is "dumped" uninhibited by import levies, it is argued the CAP is throttling agricultural business within these countries whether national or global and forcing them back into an economically stunted subsistence lifestyle. Many African and Asian dairy, tomato and poultry farmers cannot keep up with cheap competition from Europe, thus their incomes can no longer provide for their families. They end up relying heavily on imports, which are often the EU's substidized exports. Hunger as an alibi

According to the 2003 Human Development Report the average dairy cow in the year 2000 under the European Union received $913 in subsidies annually, whilst an average of $8 per human being was sent in aid to Sub-Saharan Africa. The 2005 HDR described the CAP as "extravagant ... wreaking havoc in global sugar markets". The report also states "The basic problem to be addressed in the WTO negotiations on agriculture can be summarized in three words: rich country subsidies. In the last round of world trade negotiations rich countries promised to cut agricultural subsidies. Since then, they have increased them" an outcome hinted at in HDR 2003.[27][28]

Artificially high food prices

CAP price intervention has been criticised for creating artificially high food prices throughout the EU. The recent moves away from intervention buying, subsidies for specific crops, reductions in export subsidies, have changed the situation somewhat. Although the new decoupled payments were aimed at environmental measures, many farmers have found that without these payments their businesses would not be able to survive. With food prices dropping over the past thirty years in real terms, many products have been making less than their cost of production when sold at the farm gate.

On the other hand, high import tariffs (estimated at 18-28%) have the effect of keeping prices high by restricting competition by non-EU producers. It is estimated that public support for farmers in OECD countries costs a family of four on average nearly 1,000 USD per year in higher prices and taxes.[24]

Hurting smaller farms

Although most policy makers in Europe agree that they want to promote "family farms" and smaller scale production, the CAP in fact rewards larger producers. Because the CAP has traditionally rewarded farmers who produce more, larger farms have benefited much more from subsidies than smaller farms. For example, a farm with 1000 hectares, earning one hundred extra euro per hectare will make 100,000 extra euro, while a 10 hectare farm will only make an extra 1000 euro, disregarding economies of scale. As a result most CAP subsidies have made their way to large scale farmers. Since the 2003 reforms subsidies have been linked to the size of farms, so this is not so true any more. So while subsidies allow small farms to exist, they funnel most profits to larger scale operations.

Environmental problems

A common view is that the CAP has traditionally promoted a large expansion in agricultural production. At the same time it has allowed farmers to employ unecological ways of increasing production, such as the indiscriminate use of fertilisers and pesticides, with serious environmental consequences. However a total re-focusing of the payment scheme in 2004 now puts the environment at the centre of farming policy. This forces strict limits on the amount of nitrogenous fertilisers which can be used in vulnerable areas. Strict environmental requirements must also be observed to maintain any subsidy payments.

Equity among member states

Some countries in the EU have larger agricultural sectors than others, notably France, Spain, and Portugal, and consequently receive more money under the CAP.[29] Countries such as the Netherlands and the United Kingdom have particularly urbanised populations and rely very little on agriculture as part of their economy (in the United Kingdom agriculture employs 1.6% of the total workforce and in the Netherlands 2.0%). Other countries receive more benefit from different areas of the EU budget. Overall, certain countries make net contributions, notably Germany (the largest contribution overall) and the Netherlands (the biggest contribution per person), but also the UK and France. The largest per capita beneficiaries are Greece and Ireland.

France has a slightly lower GDP than the UK, and its higher population means that it earns slightly less per person compared to the UK. Germany has a GDP approximately 25% higher than either France or the UK, but per capita income is comparable to the other two countries. France now makes a net payment into the EU budget, so it can not be said that it receives a subsidy from any other country. However, France remains the #1 beneficiary of the CAP, while the new member states receive only small financial aid.

UK rebate and the CAP

The UK would have been contributing more money to the EU than any other EU member state, except that Margaret Thatcher's government negotiated a special annual UK rebate in 1984. Without the rebate the UK was the largest contributor. Due to the way the rebate is funded, France pays the largest share of the rebate (31%), followed by Italy (24%) and Spain (14%).[30][31][32]

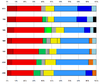

The discrepancy in CAP funding is a cause of some consternation in the UK. As of 2004[update], France received 13% of total CAP funds more than the UK (see diagram). This is a net benefit to France of €6.37 billion, compared to the UK.[33] This is largely a reflection of the fact that France has more than double the land area of the UK. In comparison, the UK budget rebate for 2005 is scheduled to be approx €5.5 billion.[34] The popular view in the UK (as, for example, set forth in the tabloid press) is that if the UK rebate were reduced with no change to the CAP, then the UK would be paying money to keep an inefficient French farming sector in business - to many people in the UK, this would be seen as "grossly unfair". French motives for generating arguments about "solidarity" and "selfishness" are therefore seen as extremely self-serving.

If the rebate were removed without changes to the CAP then the UK would pay a net contribution of 14 times that of the French (In 2005 EU budget terms). The UK would make a net contribution of €8.25 billion compared to the current contribution of €2.75 billion, versus a current French net contribution of €0.59 billion.

In December 2005 the UK agreed to give up approximately 20% of the rebate for the period 2007-2013, on condition that the funds did not contribute to CAP payments, were matched by other countries' contributions and were only for the new member states. Spending on the CAP remained fixed, as had previously been agreed. Overall, this reduced the proportion of the budget spent on the CAP. It was agreed that the European Commission should conduct a full review of all EU spending.[35][36]

CAP as a form of State intervention

Some critics of the common agricultural policy reject the idea of protectionism, either in theory, practice or both. Free market advocates are among those who disagree with any type of government intervention because, they say, a free market without interference will allocate resources more efficiently. The setting of 'artificial' prices inevitably leads to distortions in production, with over-production being the usual result. The creation of Grain Mountains, where huge stores of unwanted grain were bought directly from farmers at prices set by the CAP well in excess of the market is one example. Subsidies allowed many small, outdated, or inefficient farms to continue to operate which would not otherwise be viable. A straightforward economic model would suggest that it would be better to allow the market to find its own price levels, and for uneconomic farming to cease. Resources used in farming would then be switched to a myriad of more productive operations, such as infrastructure, education or healthcare.

Economic sustainability

Many economists believe that the CAP is unsustainable in the enlarged EU. The inclusion of ten additional countries on May 1, 2004 has obliged the EU to take measure to limit CAP expenditure. Poland is the largest new member and has two million smallhold farmers. It is significantly larger than any of the other new members, but taken together the new states represent a significant increase in recipients under the CAP. Even before expansion, the CAP consumed a very large proportion of the EU's budget. Considering that a small proportion of the population, and relatively small proportion of the GDP comes from farms, many considered this expense excessive.

How many people benefit?

Critics[37] argue that too few Europeans benefit. Only 5.4% of EU's population works on farms, and the farming sector is responsible for 1.6% of the GDP of the EU(2005)[38]. The number of European farmers is decreasing every year by 2%. Additionally, most Europeans live in cities, towns and suburbs not rural areas. However, their opponents argue that the subsidies are crucial to preserve the rural environment, and that some EU member states would have aided their farmers, anyway.

The 2007-2008 world food price crisis has renewed calls for farm subsidies to be removed in light of evidence that farm subsidies contribute to rocketing food prices, which has a particularly detrimental impact on developing countries.[39]

See also

Other articles

- Agricultural policy

- Common Fisheries Policy

- European Commissioner for Agriculture

- European Union Association Agreement

- Lobbying in the United Kingdom

- Land Allocation Decision Support System

- Protected Designation of Origin

- Single Payment Scheme

References

- ↑ Financial Management in the European Union

- ↑ "EU budget facts and myths". EU press release. http://europa.eu/rapid/pressReleasesAction.do?reference=MEMO/07/350&format=HTML&aged=0&language=EN&guiLanguage=en. Retrieved 2007-11-01.

- ↑ The Economics of Europe - Dennis Swann (pg. 232)

- ↑ Waterfield, Bruno (27 September 2007). "Set-aside subsidy halted to cut grain prices". The Daily Telegraph (London). http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/1564327/Set-aside-subsidy-halted-to-cut-grain-prices.html. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ↑ Rapid - Press Releases - EUROPA

- ↑ Wyn Grant, The Common Agricultural Policy, 1997

- ↑ EU-Commission, Directorate-General for Agriculture: Agenda 2000 – A CAP for the future

- ↑ "Sapir Report on budget reforms" (PDF). http://www.swisscore.org/Policy%20docs/general_research/sapir_report_en.pdf.

- ↑ "economist article (registration required)". http://www.economist.com/World/europe/displayStory.cfm?story_id=3722828.

- ↑ "2003 subsidy reforms". EU. http://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/capreform/index_en.htm. Retrieved 2007-11-01.

- ↑ Evaluation CMO sugar

- ↑ "EU sugar reforms announcement". EU press release. http://europa.eu/rapid/pressReleasesAction.do?reference=IP/06/194&format=HTML&aged=0&language=EN&guiLanguage=en. Retrieved 2007-11-01.

- ↑ Agriculture and Rural Development - CAP reform: Sugar

- ↑ http://www.acpsugar.org

- ↑ "Sugar reform". http://agritrade.cta.int/news0506.htm#sugar.

- ↑ "Sugar reforms". Europolitics website. http://www.eupolitix.com/EN/News/200602/4df356fd-57bd-4d87-985b-8f1357cee360.htm. Retrieved 2007-11-01.

- ↑ "top 20 cap payments". Farmers Guardian. 1 September 2006. http://www.farmersguardian.com/story.asp?sectioncode=1&storycode=4180. Retrieved 2007-11-10.

- ↑ Rural Payment Agency "Farm Payments by value 2003-2004

- ↑ "Off with their subsidies! EU threatens to slash huge annual payments to Britain's wealthiest landowners" article by Jerome Taylor in The Independent November 9, 2007

- ↑ - Conference on „Reforming the budget, changing Europe“

- ↑ - Declaration "A Common Agricultural Policy for European Public Goods" download

- ↑ Potočnik calls for 'profound greening' of EU farm policies EurActiv 17 March 2010

- ↑ "Sweden proposes abolition of farm subsidy". http://www.thelocal.se/7443/20070529/. Retrieved 2007-11-01.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 The Doha Development Round of trade negotiations: understanding the issues

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 http://openeurope.org.uk/media-centre/summary.aspx?id=256

- ↑ http://caphealthcheck.eu/return-of-the-butter-mountain/

- ↑ http://hdr.undp.org/en/media/hdr03_complete.pdf

- ↑ http://hdr.undp.org/en/media/HDR05_complete.pdf

- ↑ - www.ecipe.org: study examining current subsidy distribution and criteria for future subsidy allocation across member states

- ↑ Arrogant and hypocritical Chirac savaged by British press

- ↑ The Daily Telegraph (London). http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/main.jhtml?xml=/news/2005/06/11/weu11.xml&sSheet=/news/2005/06/11/ixnewstop.html. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ↑ The Daily Telegraph (London). http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/main.jhtml?xml=/news/2002/10/23/wchir23.xml. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ↑ "Q&A: Common Agricultural Policy". BBC News. 20 November 2008. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/4407792.stm. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ↑ "Q&A: The UK budget rebate". BBC News. 23 December 2005. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/4721307.stm#howbig. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ↑ "Key points of the EU budget deal". BBC News. 17 December 2005. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/europe/4537912.stm. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ↑ http://ue.eu.int/ueDocs/cms_Data/docs/pressData/en/misc/87677.pdf

- ↑ - www.reformthecap.eu: arguments for fundamental CAP reform and links to relevant studies

- ↑ Turkey in Europe: Breaking the Vicious Circle. , 2009. Web. 30 Apr 2010. <http://www.independentcommissiononturkey.org/pdfs/2009_english.pdf>.

- ↑ EurActiv.com - Food crisis set to weigh on CAP reform | EU - European Information on Sustainable Dev

External links

General information

- European Union: Agriculture

- farmsubsidy.org Searchable database of the recipients of CAP subsidies, using data obtained by access to information requests to EU member state governments

- The Common Agricultural Policy - CAP European Navigator

- rpa.gov.uk past and present UK subsidy schemes

Opinions

- Reform the CAP An overview of the arguments for CAP reform with links to the most important studies

- EU Report on effects of expansion of the EU on farm production

- A public health point of view on CAP

- LADSS - CAP Reform: Case study analysis of the impact of CAP

- New Zealand's hardy farm spirit from BBC correspondent John Pickford

- Green and Pleasant Land

- CAP Health Check CAP reform: Analysis and opinion from European researchers, academics and policy-makers

- Is the EU CAP boosting deforestation? Some background info on why the EU is lacking creditability in case of its programs to combat deforestation and illegal logging

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||